It happened in an economics class during his fourth year at the University of Alberta. The professor called out Harlan Pruden, then 26, for wearing a baseball cap, saying: “Where I come from, gentleman remove their hats when they come inside.”

Pruden responded: “Right. And where you also come from, me as a gay native would not be sitting here at this table.”

Harlan Pruden (The Globe and Mail)

The interaction led Pruden to critically evaluate the content he was learning in a broader context. “I realized there was no attentiveness to class, no attentiveness to race and gender, and of course no attentiveness to sexual orientation,” he says now.

It proved to be one of the pinnacle moments of his life. He dropped out of university and moved to New York City where he completed an undergraduate degree at New York University and went on to work in the community development sector for 20 years.

Moving to the U.S. was a profound change for Pruden, who was raised in Canada. Pruden is from the Whitefish Lake First Nation, and grew up on Beaver Lake, his mother’s community in Alberta.

In 2003, he attended a Two Spirit Gathering in Oklahoma, an event attended by Indigenous and Two Spirit individuals that engaged in talent shows, powwows, and educational workshops. It was there that Pruden recalls for the first time not having to count the number of people he thought were like him to determine if he was safe. “It was so affirming of my entire being, that the entire space, no matter where I went, was deemed a safe space.”

But he still felt a sense of alienation.

The beginning of the conversation

Two Spirit refers to members within all Indigenous nations who are fluid with their gender or sexual orientation, or both. While each nation has a specific term for their Two Spirit members and defines their roles differently, Two Spirit was adopted as a universal term in 1991 at the third annual Intertribal Native American, First Nations, Gay and Lesbian conference in Winnipeg.

“Often we position and operationalize Two Spirit as an identity, but it becomes highly problematic because when positioned as an identity it becomes an endpoint – where the answer to a call of Two Spirit should be the beginning of the conversation, ultimately leading you back to your nation and your ways,” says Pruden. He describes Two Spirit as a way to organize community members that adopt non-binary gender roles.

Unlike Western society, 155 Indigenous nations have documented multiple genders – some have three while others have up to seven. While members of the LGBTQ community ‘come out’ to family and friends, Two Spirit individuals ‘come in’. “The coming in process as an Aboriginal person who is LGBTQ comes to understand their relationship, place, and value within their own family, community, culture, and history,” he explains.

Now, Pruden lives back in Canada and is three years into a PhD program at the University of British Columbia. He acknowledges that while public awareness of Indigenous communities has improved, Indigenous students must still endure a Eurocentric educational framework – one that is especially challenging for Two Spirit students who are further ostracized based on their sexuality.

Colonial suppression of gender

Prior to colonization, Two Spirit members were accepted and respected within their communities. When European settlers arrived, they forced heteronormativity which led to a suppression and erasure of alternative expressions of sex and gender.

David Kirk from Capilano University (North Shore News)

But even during a widespread revitalization of Indigenous culture and language in the 1960’s and 1970’s, Two Spirited people were largely excluded. In the 1990’s, a movement emerged that involved a reclaiming of the role and confronting of stereotypes; Two Spirit people began making their presence known.

Yet a lack of representation in the academic environment remains. As an undergraduate student, Pruden believes he felt discouraged because he didn’t see himself in the material he was studying, in university faculty, or in campus spaces.

For David Kirk, a First Nations faculty advisor and educator at Capilano University in British Columbia, Pruden’s concerns are all too familiar. “You go to these places [educational institutions] and you go, ‘well, I don’t identify with anything that’s here, why would I want to go?’”

Kirk is a Two Spirit member of the Stó:lō Nation who has worked at Canadian educational institutions for years. He notes that while many universities have Indigenous Elders available for support, some Two Spirit students may not be comfortable addressing an Elder. “Many of our Elders attended residential school and had been influenced and impacted by the Christian dogma that’s taught. It’s created a sense of uncertainty—can you be open? As a Two Spirited person, are you going to be accepted?” Even he was initially hesitant to reveal himself as Two Spirit to the Elders at Capilano University, he adds.

Both educators believe that having more Two Spirit faculty would not only provide students with supportive leaders, but increase the amount of research dedicated to the Two Spirit community.

“It is an honouring and a celebration of other’s differences that unites and brings us together,” Pruden says, adding that despite being a student in Western educational institutions over many years, his mind remains un-colonized – which is what allows him to be an advocate for his community.

“We are a living, breathing culture that have been adaptive – and that adaptiveness is a testament, not only to our survival skills but our resistance.”

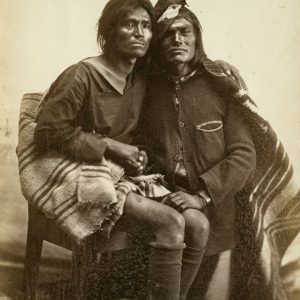

Pruden is assessing historical images of Two Spirit people as part of his PhD research.

Jennifer La Grassa is a Master of Journalism candidate at Ryerson University.