Russell Fayant’s Old One [the term he uses for ‘elder’] once gave him a challenge.

“What are you doing to save this language?” he asked.

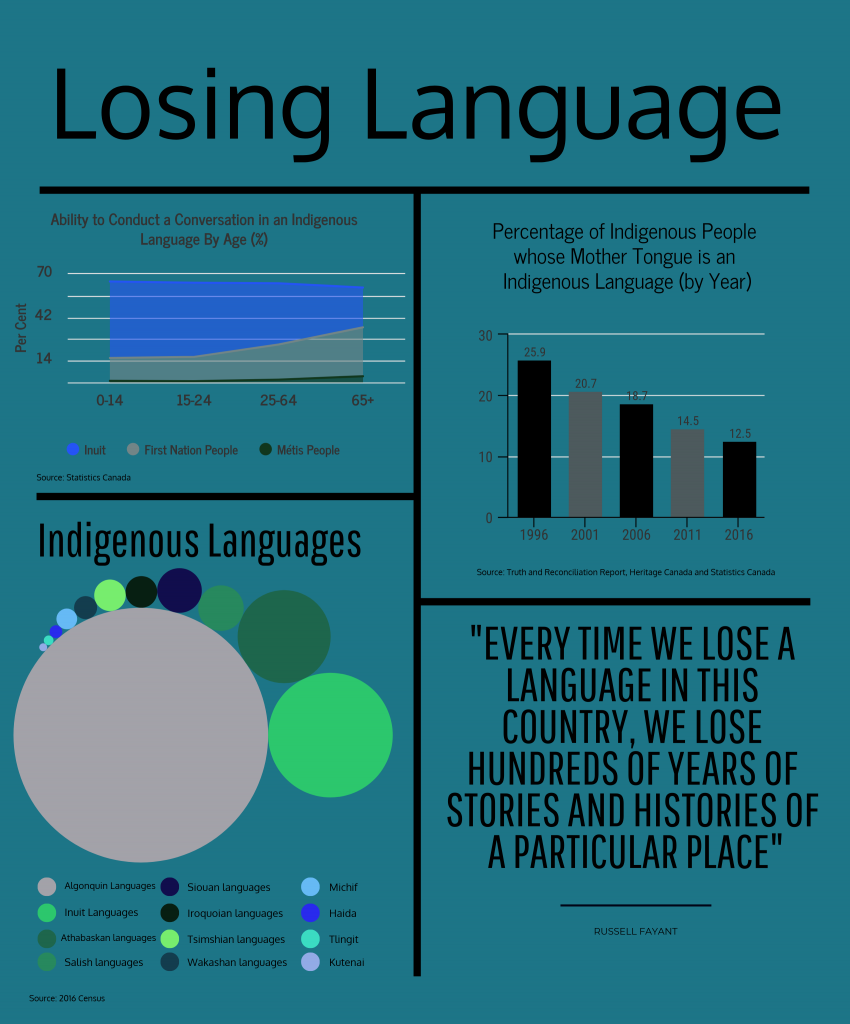

The language in question was Michif. It is the language of the Métis people of Canada and the United States and is a mix of Cree and French. Currently, only 1,170 people in Canada speak Michif.

In response, Fayant decided to introduce Michif language classes in the Saskatchewan Urban Native Teacher Education Program (SUNTEP) at the Gabriel Dumont Institute, a semi-autonomous institution connected to the University of Regina.

The effort to save the Michif language is an urgent one. According to the 2016 census, less than two per cent of Métis people speak an Indigenous language – down from 2.5 per cent in the 2011 census.

“There are 300,000 Métis people across Canada and if there are only 1,000 people speaking [Michif] fluently, then I would consider that at the verge of extinction. I think a lot of linguists would as well,” Fayant says.

“If people my age don’t become fluent within the next ten to 15 years, then the only hope for us is to learn this language from books. It’s literally this generation or it’s gone.”

Fayant serves as a facilitator for the class, but not as the instructor of the language as he is not fluent in Michif. He, too, is learning it along with the students.

Erma Taylor, a Métis Old One and an administrator for SUNTEP, teaches the language to the class. Michif speakers are dying at an “alarming rate”, she says.

Since the Métis defeat in the North-West Rebellion of 1885, which saw some Métis people in Saskatchewan rebel against the Canadian government of former (and first) Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald for protection of their land, the Michif language has been in decline. The Canadian government has since associated all Métis people with the rebellion. Everything associated with Métis culture was seen as rebellious, including the Michif language. As a result, Métis people felt compelled to hide their language and only speak it in secret.

Stories, songs, legends and histories, first recorded and understood in Michif become whitewashed by the colonizer’s tongue and this lack depth, humour and context.

— Russell Fayant

Consequently, parents did not pass Michif down to their children, thinking they would have an easier life if their mother tongue was not Michif. “It’s really sad and unfortunate, but they were doing what they thought was guaranteeing their survival,” Fayant says.

Much more than just the language was lost. There are numerous stories in Michif that lose their meaning and impact when they are translated to English. In an academic article Fayant co-authored on the SUNTEP’s Michif classes, Fayant writes, “Stories, songs, legends and histories, first recorded and understood in Michif become whitewashed by the colonizer’s tongue and this lack depth, humour and context.”

“They [Métis people that don’t speak Michif] are missing out on a huge part of the culture,” Taylor adds.

But there is a larger reason for all of Canadians to care about the preservation of Michif – reconciliation. “Michif for me, as long as Metis people in general, represents the truest and purest form of reconciliation this country has even seen,” Fayant says. “What better example of reconciliation is there than a language that equally represents a French, an English and a Cree worldview? If we lose that, not only is that a loss for us as Metis people in a cultural sense, it’s a loss for all of Canada because we lose that important model.”

SUNTEP’s classes are partly taught in classrooms and partly taught in Métis communities where the students can be surrounded by Michif speakers and immersed in the language. In the classroom, the language is taught similarly to any other second language class with a focus on learning through repetition of words and phrases. In the field, the class speaks with Métis Old Ones and participates in Métis cultural activities, like baking and listening to oral stories.

“We speak Michif in the class, in the hallways. We’ll greet each other in Michif. If we come into the office or see our teachers or Russell, we try to speak a little bit of Michif [with them],” says Danielle Pelletier, a second year Métis student in SUNTEP and a student in the Michif language course.

Danielle Pelletier wants to use her training in the course to be able to teach Indigenous students Michif as a teacher. “I really hope to teach in a community school or a reserve school, where I am with Indigenous students and helping them reclaim their culture – and become proud again of who they are.”

Neil Robert Moss is a Master of Journalism candidate at Ryerson University. He graduated from the University of Ottawa with a degree in history and is currently interning at The Hill Times.